In the rolling hills just outside Washington, D.C., a small fort once stood watch over a community few remember today. Freedom Hill, a settlement of free Black families in Fairfax County, was born out of the manumission economy and thrived within a day’s ride of the capital. Its residents lived in the shadow of powerful Confederate neighbors, yet they raised Union flags during the Civil War, built their own institutions, and resisted in ways history rarely tells. From the camps that inspired Julia Ward Howe’s Battle Hymn of the Republic to the capture of Confederate scouts at the fort, Freedom Hill’s story is a tapestry of resilience, espionage, and legacy.

Freedom Hill: A Story of War, Resistance, and Legacy in Fairfax County

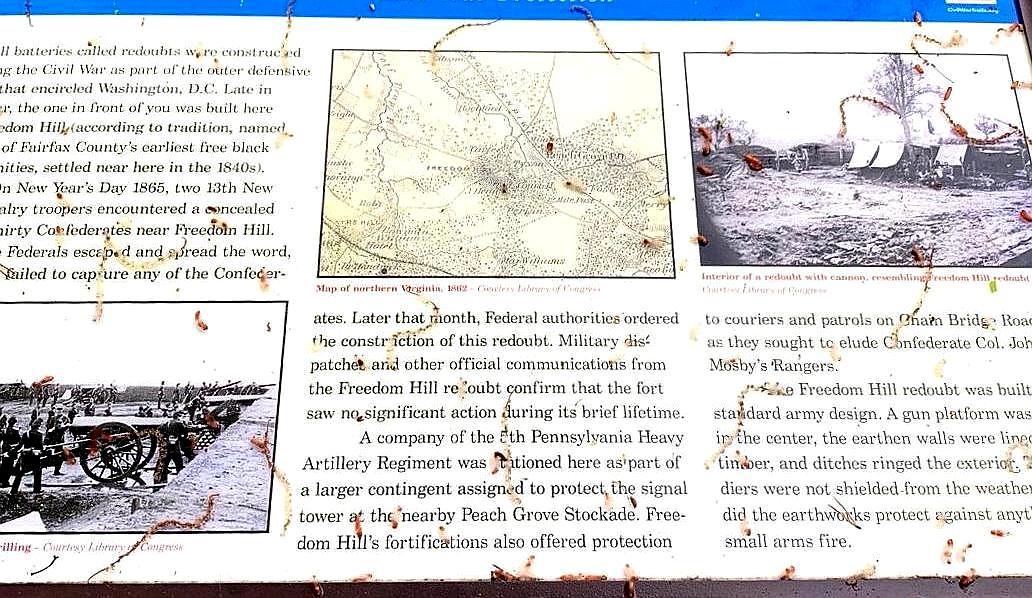

This is the historical marker inspiring this post. It is located at the Freedom Hill Redoubt in Vienna, Virginia, within Freedom Hill Park. It’s part of the Virginia Civil War Trails network and sits just off Chain Bridge Road, not far from Tysons Corner.

The Battle Hymn and the Defenders of Washington

In the fall of 1861, Julia Ward Howe visited Union Army camps just outside Washington, D.C. She saw men in tents, mud on their boots, rifles propped beside campfires — soldiers ready to defend the capital. They sang “John Brown’s Body” with such conviction that Howe, inspired by their determination, penned The Battle Hymn of the Republic.

Those same kinds of camps dotted the countryside from the Potomac River into Fairfax County. Among them, late in the Civil War, was a small earthen fort near today’s Tysons Corner — the Freedom Hill Redoubt — built to protect the approaches to Washington from Confederate raiders.

The Freedom Hill Community

The redoubt overlooked Freedom Hill, one of Fairfax County’s earliest free Black communities. Settled in the 1840s, its residents included both African Americans who had bought their freedom and those emancipated by their enslavers. Many had been enslaved by the same white families who dominated the Fairfax County Courthouse before the war.

Freedom Hill’s residents built homes, cultivated small farms, and lived with remarkable independence. During the war, they openly flew Union flags — a bold statement in a county where the wealthiest white families supported the Confederacy. Yet, some white neighbors quietly favored the Union, knowing their livelihoods depended on trade with Washington.

The First Fairfax Courthouse and Black Landownership

Freedom Hill’s story connects to the very origins of Fairfax County. The first courthouse, built in 1742 near Tysons, stood on Indigenous land. In 1752, it burned down — according to oral history, set aflame by Keziah Hatton, an ancestor of Lucy Carter, in protest against its illegal construction. The county seat moved, but decades later Keziah’s descendants, both Black and Indigenous, returned to reclaim land in the same area.

By the 19th century, Fairfax County had several free Black settlements — Gum Springs, Odrick’s Corner, and communities in Vienna, Lewinsville, and Frying Pan — all within a day’s travel of Washington, D.C. That proximity fostered strong economic and social connections. Free Black residents worked in the capital, shared news, and sometimes acted as couriers or informants for the Union.

The Manumission Economy in Fairfax

Freedom Hill existed because of Fairfax’s fragile manumission economy — a system where enslaved people were freed by will, deed, or by purchasing their own liberty. Before 1806, Virginia allowed manumission without major restrictions, and Fairfax’s Quaker and Methodist influences encouraged it. After 1806, freed people were required to leave Virginia within a year unless they received special permission to stay.

Families who navigated these laws sometimes acquired land, creating pockets of independent Black life in the midst of slavery. Freedom Hill’s residents were part of that legacy — holding title to land, paying taxes, and building self-reliance long before the Civil War.

The 1865 Capture of Confederate Scouts

In January 1865, Union troops captured thirty Confederate scouts near Freedom Hill. Local tradition links them to Confederate partisan raiders, possibly from John S. Mosby’s Rangers.

John Singleton Mosby, the “Gray Ghost,” led the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry — a Confederate guerrilla unit famous for lightning raids in Northern Virginia. Modern historians see him as a brilliant tactician but also as a commander whose men blurred the line between soldier and outlaw. They targeted Union supply lines, couriers, and sometimes civilian Unionists — including Black communities like Freedom Hill, whose loyalty to the Union was well known.

Lucy Carter: A Free Woman and Possible Spy

One of Freedom Hill’s most remarkable residents was Lucy Carter, a free woman of color in the mid-19th century. She carried manumission papers to prove her legal status, a necessity in a state where free Black people could be seized and sold into slavery.

In 1864, Lucy was granted special passes by a Union cavalry officer, allowing her to travel through military lines — a privilege usually reserved for trusted scouts or messengers. Some historians believe she may have served as a Union spy, moving between Fairfax and Washington with information about Confederate movements.

Keziah Hatton’s Legacy

Lucy Carter’s courage was part of a family tradition. Her ancestor Keziah Hatton had defied colonial authority a century earlier by destroying the county’s first courthouse. This act of resistance against land theft and injustice became part of the Carter family identity. By the time of the Civil War, the Carters were landowners on ground once taken from them, living within sight of Union forts and in the shadow of Confederate hostility.

The Role of Women in Resistance and Survival

Women like Lucy Carter and Keziah Hatton show how resistance wasn’t always on the battlefield. It was in quiet defiance — reclaiming land, preserving family autonomy, passing on oral history, and making dangerous choices to aid the cause of freedom. In Fairfax County’s history, these women are threads connecting colonial resistance, the fight against slavery, and the struggle to preserve Black communities in the face of postwar racial and economic pressures.

Legacy

Freedom Hill’s story is more than a local footnote. It’s a testament to the resilience of free Black Virginians, the complexity of Civil War loyalties in Northern Virginia, and the enduring power of family legacy. From Julia Ward Howe’s hymn to Lucy Carter’s wartime service, this history reminds us that the battle for freedom was fought in camps and courthouses, on hillsides and in homes — and that some of its bravest soldiers never wore a uniform.